Pastels and Resilience

Saved Miami Beach’s Deco History

Picture this: It’s the 1930s, and Miami is waking up to a new era. The sun is

rising over South Beach (SoBe), casting a golden glow over rows of

pastel-coloured façades. Palm trees sway in the ocean breeze, and neon lights

icker to life as the night sets in. There’s an energy in the air — crisp and

optimistic.

This was the birth of Miami’s signature Art Deco identity — a design language

that would transform a weathered coastal town into one of the world’s most

recognisable architectural icons.

A postcard of Miami’s Commodore Hotel;

All pics courtesy MDPL, Barbara Baer Capitman Archives

EXHIBITION THAT BIRTHED DECO

The first glimmer of a design style that would later be identied by the moniker ‘Art Deco’ was seen at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes (International Exposition of Decorative Arts and Modern Industries) of 1925. This was a landmark exhibition spanning 57 acres bang in the centre of Paris and housing mostly French and European pavilions displaying a string of modern design styles. The most dominant among these? French art moderne, later called Art Deco after this exposition that gave it global fame.

While the pavilions of countries and architects including Le Corbusier (well known in India for his modern urbanism experiment with designing Chandigarh in 1947 on Jawaharlal Nehru’s commission) reected modernist styles, the pavilions of furniture designers like Jacques-Emile Ruhlmann and French department stores like Galeries Lafayette and Le Printemps were embellished with Deco sunbursts, dramatic geometric patterns and stepped setbacks. Their interiors spelt luxury, with rooms housing modern consumer products. If there was a nation that dened chic taste, it was France.

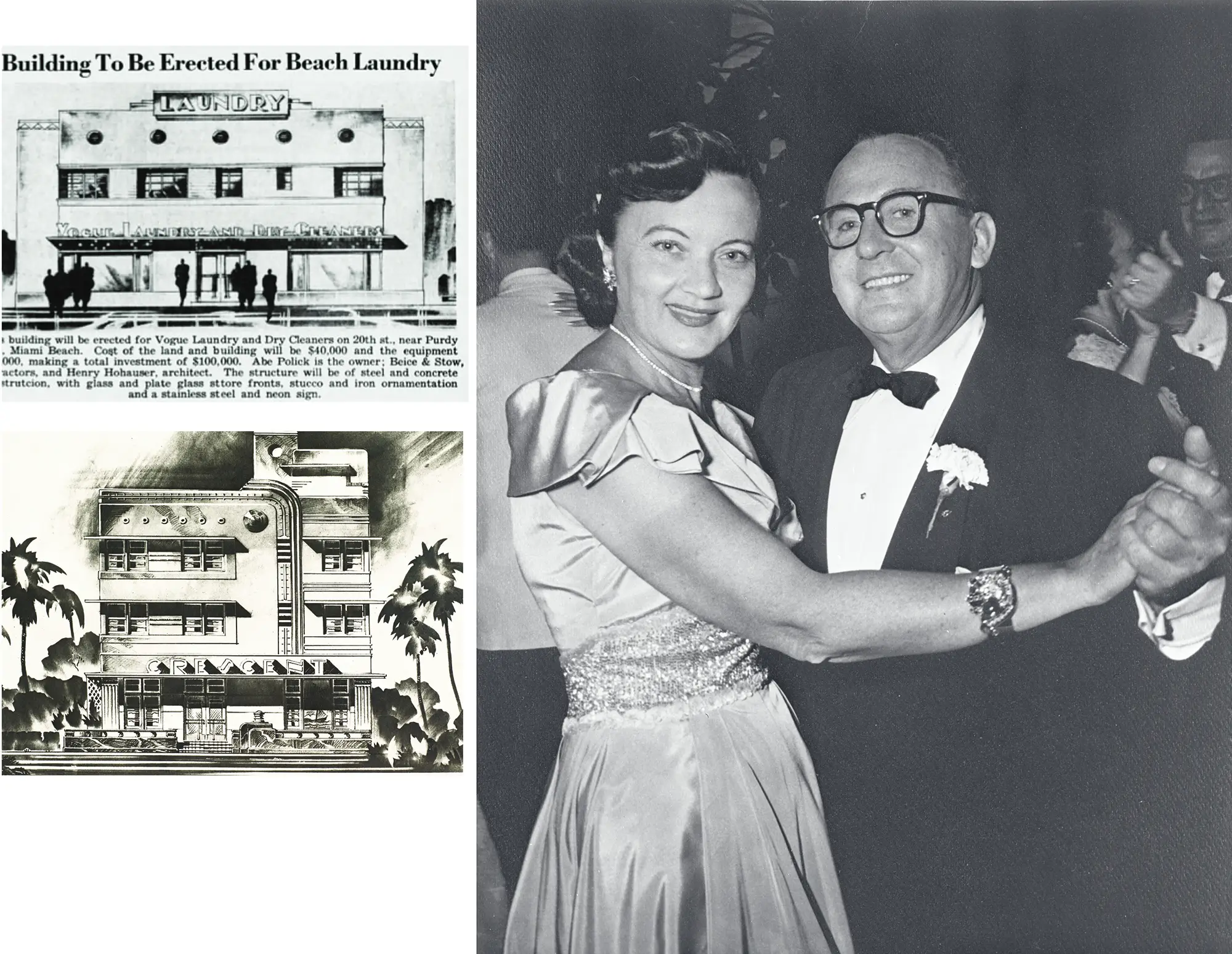

- Miami’s star architect Henry Hohauser with wife Grace

- A sketch of Crescent Hotel designed by Henry Hohauser

- A newspaper cutting announcing the construction of Miami Beach’s Vogue Laundry and Drycleaners designed by Henry Hohauser using the new favourite materials of the Deco era – steel and concrete – with a fashy neon sign

DECO COMES TO MIAMI

In the interwar years, the Art Deco architecture and design style had made its way to America, inuencing New York’s Empire State Building and Rockefeller Center, and eventually reached Miami’s shores.

By the early 1930s, amidst economic hardship, Miami embraced a local offshoot of the style known as Tropical Deco — a graceful infusion of Streamline Moderne with shell and palm tree motifs, curves and porthole windows reminiscent of ocean liners. Miami Beach was once a swamp built over by entrepreneur Carl Fisher who envisioned it as a glamorous vacation hub for the moneyed. The goal was to yank America’s real estate industry out of depression through speedy construction of uniform Reinforced Cement Concrete (RCC) buildings with a similar design footprint.

Behind Miami Beach’s almost 800 Deco inspired structures were architects Henry Hohauser and L. Murray Dixon, who led the charge for this playful but classy style. Hohauser, arriving from New York in 1932, gave Miami buildings its iconic curved edges, layered roofines and lively ‘eyebrows’ above windows. Dixon’s sleek hotels added verticality and neon glamour to the skyline, creating a vivid, forward-looking architectural identity. Here, Art Deco wasn’t just about geometric, sharp edges and symmetry; it was about creating an atmosphere, soft, vibrant, and perfectly suited to the sunshine

Miami Beach’s Lincoln Theatre designed by Scottish-born American architect Thomas W Lamb in Deco style has a connect to Mumbai’s Metro cinema (Marine Lines), also designed by him. Lincoln Theatre has since changed avatars from cinema to concert hall to retail space

STORM THAT CHANGED EVERYTHING

Just as Miami’s architectural dreams were taking shape, tragedy struck. In September 1926, the Great Miami Hurricane devastated the city, flattening buildings and bringing the real estate boom to a screeching halt. But in its aftermath, came an unexpected opportunity — the chance to rebuild Miami’s identity from the ground up.

In the wake of the storm, rebuilders turned to the fresh and optimistic Art Deco style. Pastel buildings with reinforced, streamlined forms (apt for hurricane-prone coasts) and ocean liner aesthetics soon arose along Ocean Drive and Collins Avenue. These new structures signalled both, resilience and reinvention.

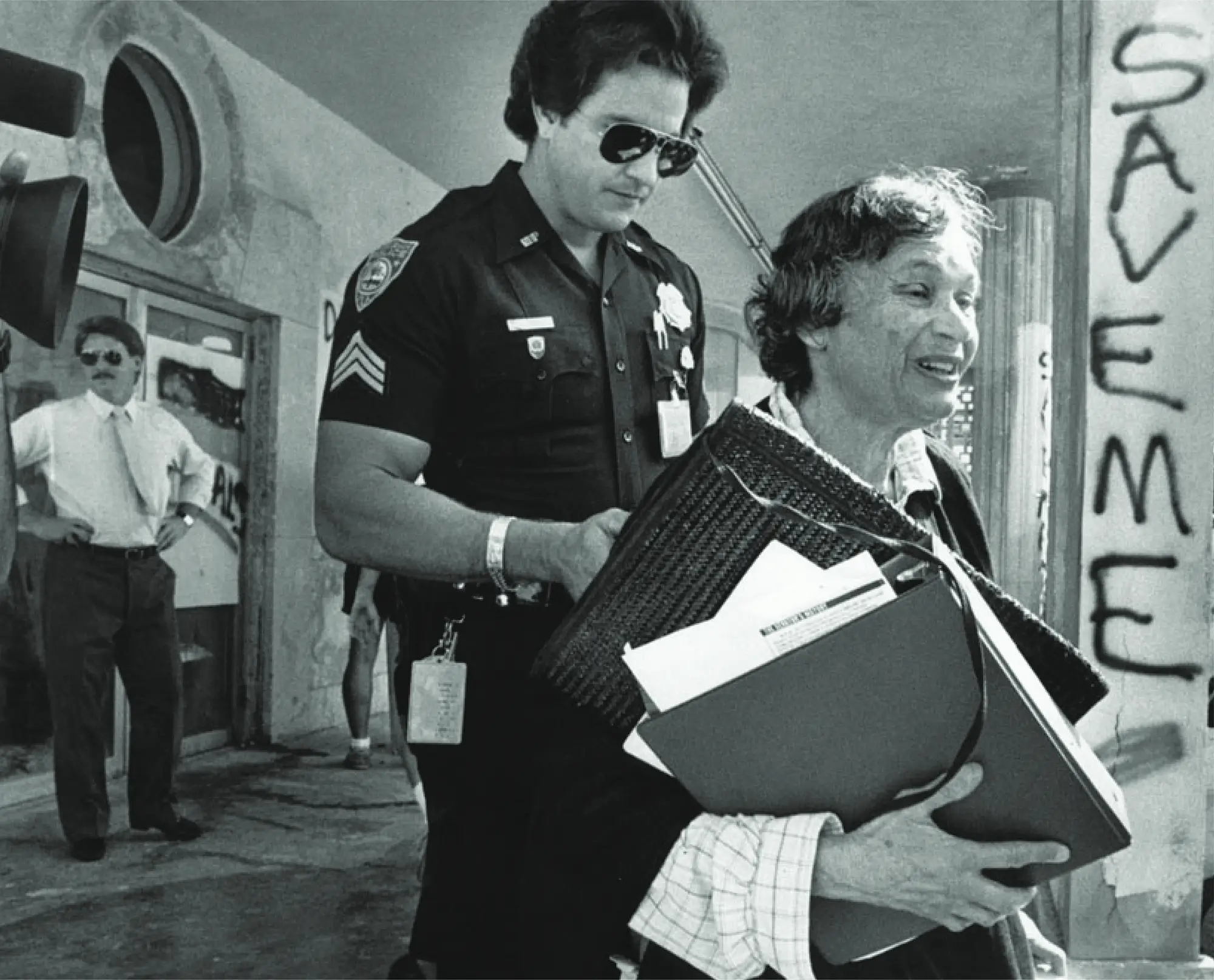

Miami’s charming buildings with Deco accents faced demolition in the 1970s and 80s when real estate pressures and infrastructure development threatened their survival.

FIGHT TO SAVE PARADISE

The glory lasted half a decade. By the 1970s, South Beach’s pastel paradise was losing its vivacity. Aging Deco structures appeared outdated and crumbling, becoming perfect prey for modern infrastructure development.

Florida would have lost its Deco gems if not for a ery preservationist. In 1976, Barbara Baer Capitman together with a group of preservationists founded the Miami Design Preservation League (MDPL) to champion the cause of salvaging these architectural gems that were now occupied by an ageing population. Capitman lobbied political representatives and real estate giants, held vigils, and galvanised the support of the community. In 1977, the Art Deco Historic District was formally established, protecting some 800 buildings between 5th and 23rd Streets — forming the largest concentration of Art Deco architecture in the world.

Miami preservationist Barbara Baer Capitman is escorted by the police out of Senator Hotel where she and other protestors chained themselves to the building to prevent its demolition. MDPL managed to delay its tearing down by a year until it was demolished in 1988. The Art Deco gem was built in 1939 with a stepped ziggurat parapet roofine, continuous eyebrows around the corners of every floor and pothole windows on the third floor.

CARDOZO SETS THE TONE

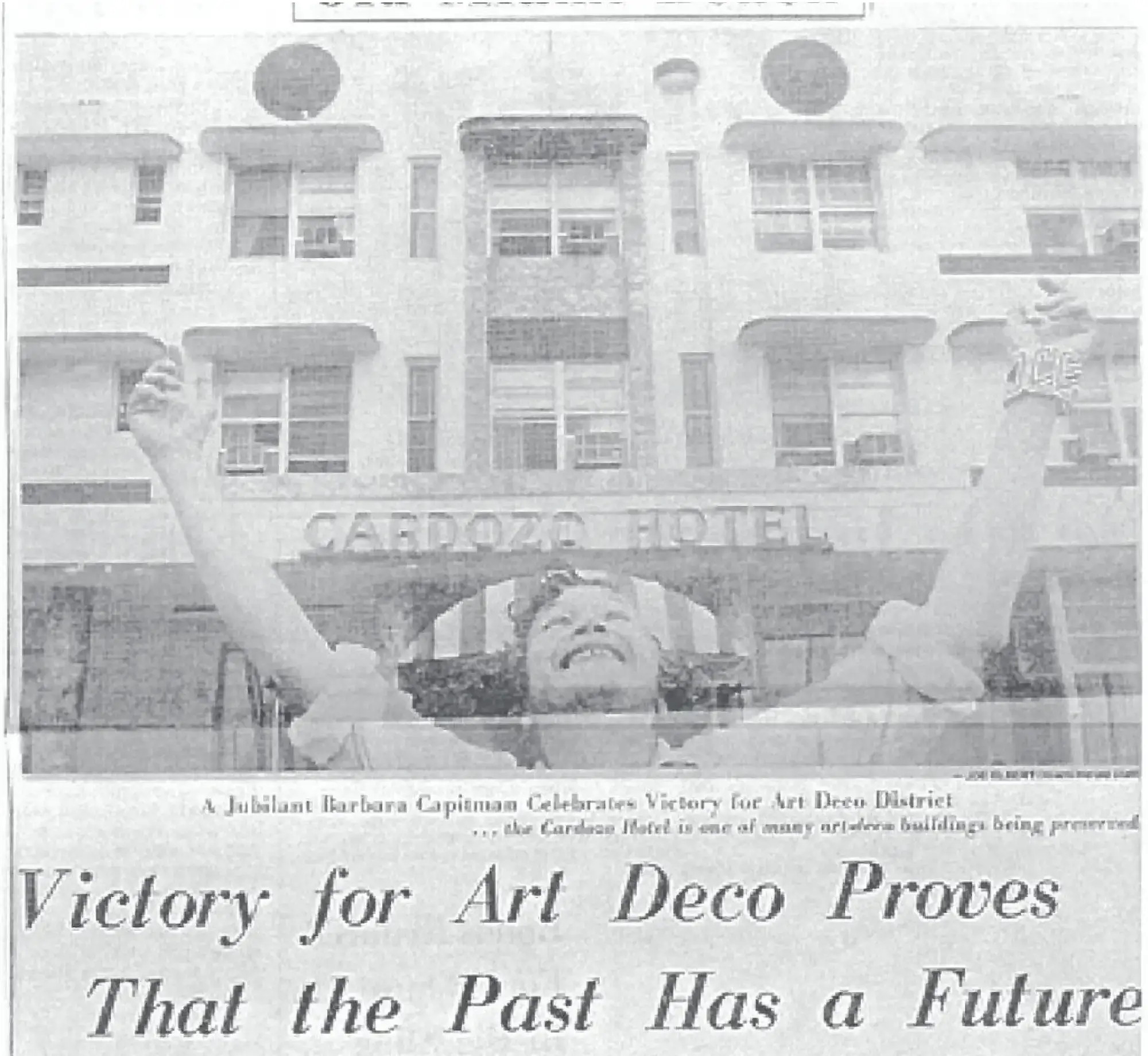

The Cardozo Hotel, in a sense, represented the potential of South Beach to turn into a lively tourist hub. In the 1970s, it was occupied by senior citizens. In 1981, it opened the Cardozo Cafe with refurnished interiors, a neon sign, and soon became the hangout for artists, poets, dancers and directors. As an article in the Miami Herald predicted, it proved “to be a true pioneer in the nancial and cultural revival of the Beach’s Art Deco district”. Interestingly, MDPL’s oce moved in here, and the creative minds including artist Woody Vondracek moved into its rooms, creating some of the most iconic Art Deco design posters, including one for Cordozo that read: Come Back to the Sea.

In June 1984, property owners in the District signed a petition to alter the zoning ordinance on Ocean Drive to allow for reasonable commercial use including for cabarets, restaurants and clubs. This eventually decided the future of commerce along Ocean Drive’s Historic District.

A jubilant Barbara Capitman celebrates the victory of her preservation struggle. In the backdrop is the Cardoza Hotel, which saw a new lease of life in 1981 when the Cardoza Cafe opened here, representing a return to the Deco District’s cafe society that was around 40 years prior. The new cafe’s menu stated: [The] new cafe is, “the focal point in the restoration of the Cardozo Hotel, the ocial pilot project of the new Art Deco District…”

FIGHT TO SAVE PARADISE

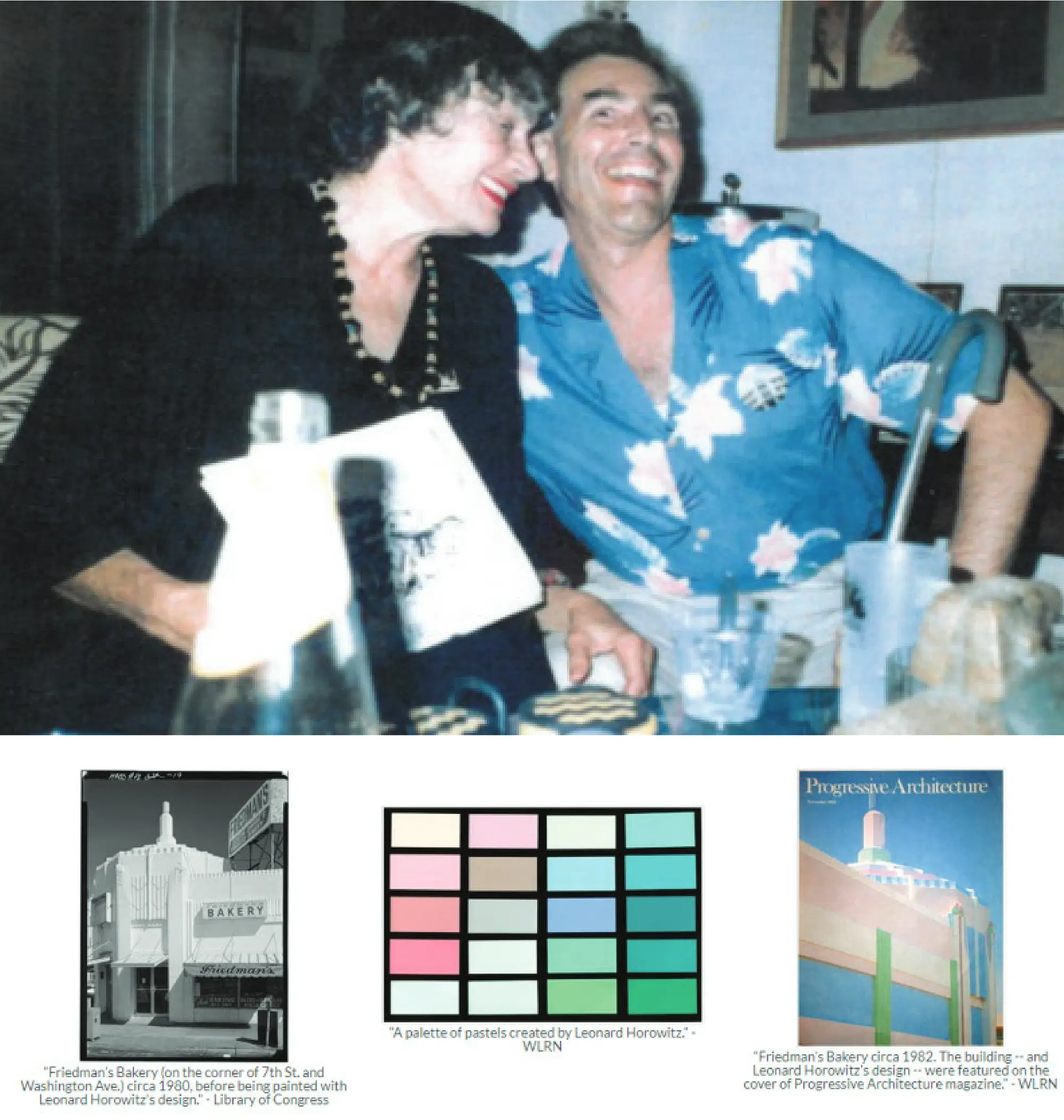

Capitman’s good friend, artist Leonard ‘Lenny’ Horowitz joined the ght to save the decrepit one square mile of of South Breach by listing it on the National Register of Historic Places. The openly-gay gentleman who once designed window displays for Bloomingdale’s moved to South Beach to live with his mother, and became Capitman’s most trusted condant despite a 30-year age dierence. They organised gala fundraisers and prostrated before bulldozers to stop demolition. They were peculiar to most but a force to reckon with, determined to turn the lower end o Miami Beach into the ‘Riviera of the South’.

Horowitz decided that they would paint South Beach’s tired buildings in the most charming tropical pastel shades of amingo pink and sea foam green. “I formulated my palette on the basis of sunset, sunrise, the summer and winter oceans and the sand on the beach, which used to be much more golden,” he said, “They all are natural sources, and they are the same ones that the original designers used. Within them are an innite variety of pastels.”

Horowitz created a characteristic colour palette and introduced it to the director of community development. The white structure of Friedman’s Bakery on the corner of 7th and Washington Avenue was picked as the edice of trial. But it was in 1985 that the breakthrough moment arrived when the roof of the Breakwater Hotel was picked as the location for the now iconic commercial for Calvin Klein’s perfume, Obsession. Every building now wanted to bask in pastel limelight. South Beach was now a tourist hub with heritage value, ready to stand up to real estate sharks. Horowitz died of AIDS in 1989. A year later, Capitman died of congestive heart failure. South Beach’s Art Deco heroes have been honoured — he with a street (11th Street) named after him, and she, a memorial in Lummus Park that features her bronze bust from a sculpture made by her mother and artist Myrtle Bachrach Baer which was interestingly created in 1939 when Capitman was just 19.

- Friends and preservationists Barbara Capitmnan and Leornard Horowitz

- Friedman’s Bakery before the colour wash; Horowitz’s colour palette; Friedman’s Bakery makes it to an edition of Progressive Architecture after its facelift

SOBE TODAY: WHERE HISTORY MEETS LIFESTYLE

Today, Miami’s Art Deco district is alive and buzzing. By day, the sun bounces o curved balconies and glass-block windows. By night, neon signs light up Ocean Drive as a rush of locals and tourists sip cocktails on rooftop terraces, framed by the very buildings that shaped Miami’s story. The annual Art Deco Weekend Festival draws thousands of visitors every January, proving that this isn’t just about nostalgia – it’s a living, breathing design culture that continues to evolve.

Art Deco Alive!’s Miami edition scheduled from October 8 to 12, 2025, will honour these very stories of resilience, imagination, preservation and community spirit.